by Devin Taylor

Can you imagine putting a stamp on your school work and sending it through the mail?

Well, that’s what school children living in Los Angeles did in 1918. When schools began to close temporarily due to widespread cases of a deadly new influenza, the city of Los Angeles created “mail-in” homework assignments for students to complete at home. You could say these students were Distance Learning Pioneers!

Learning from home would be a lot different without our modern technology. Thanks to the magic of applications like Zoom we can see and hear each other no matter where we are. We can communicate and access information instantly. We can interact in real time.

No, of course it isn’t quite the same, and there are a lot of pieces missing. Virtual learning will never replace the interpersonal connection between teacher and student. And because we are a social animal, alive in the physical world, there is no virtual setting that will adequately foster complete social learning. There is also a notable disadvantage for students who require direct, individual support to access their education. These are valid concerns that are shared by everyone involved in the education of students.

Many of the concerns we have today are things that people worried about over one hundred years ago. Newspaper editorials from the Fall of 1918 reveal familiar anxieties of citizens, school boards, and school officials. They worried that idleness among school children would undo all of the good done during the school year. They questioned the economic sustainability of paying teachers during the closure. They worried about what would happen to the community without those supports that had always come from their local school.

.jpg?mask=2) As the pandemic spread across the nation and around the world, much of that world was engaged in the first world war. Between this and the pandemic, food shortages and food insecurity became a widespread problem. The Bureau of Education launched a campaign to engage students in gardening, and President Wilson encouraged school age children to start their own gardens at home.

As the pandemic spread across the nation and around the world, much of that world was engaged in the first world war. Between this and the pandemic, food shortages and food insecurity became a widespread problem. The Bureau of Education launched a campaign to engage students in gardening, and President Wilson encouraged school age children to start their own gardens at home.

Gardening is a great, hands-on way for students to learn about agriculture and the food system. It continues to be used in school curriculum today. Children who started gardens could grow food for their own family’s consumption and school districts could volunteer to contribute at the community level.

Not unlike today, schools in 1918 played an important role in supporting the community during a time of crisis and economic hardship. Understandably, most people did not want schools to close. Here in Minnesota, local health departments met initial resistance from school boards, parents, and superintendents. A letter from a parent to the Minneapolis superintendent, B.B. Jackson, states:

“I take great pleasure, in endorsing your courageous stand, in protesting strongly against the arbitrary, and unfair closing of our public schools.”

This was in response to the superintendent’s order that students return to school on October 21, following the order from the health department to close all Minneapolis schools by October 12. In the end, a peaceable resolution was achieved and the school board sided with the health commissioner, and schools were once again closed, resulting in a significantly lower death toll than the neighboring St. Paul.

The city of St. Paul did not close schools until November 6, and chose to reopen just eleven days later, after a slight decline in daily reported cases. But as schools and businesses reopened, a second wave of illness came through and Minnesota schools were forced to close again on December 10. According to St. Paul Health Department records, a significant number of second-wave cases were among school-age children and teachers.

More on the respective response of Minneapolis and St. Paul can be found in Greg Abbott’s article The Spanish Flu in the Twin Cities (Minnesota School Boards Association Journal).

But what was happening outside of the Twin Cities, as the second wave spread?

Across the country, health commissioners ordered schools to close, along with theatres, churches, and other public gathering spaces. Schools were closed in Seattle and several other Washington cities, as well as major cities like Los Angeles and Cleveland, Ohio. Cleveland and Los Angeles have since been noted for their educational innovations that were reportedly unmatched by other states. Home-school projects and mail-in homework assignments kept both students and teachers academically relevant, and may have kept many older students from entering the war in the absence of school.

In other parts of the country, education began to look a bit more like trade school or apprenticeship. The Boy’s Working Reserve, organized by the US Department of Labor, enrolled students on “enforced vacation” to work in agriculture, manufacturing, and shipping. This provided structure and the opportunity to learn a trade. (Though, there was probably not much room for social distancing for those who found themselves assigned to the manufacturing sector!) One editorial from The Journal of Education claimed: “In many ways the pandemic has been highly educative.”

So what did teachers do while the school doors were closed?

Without Zoom, Seesaw, and Gmail, it was harder for teachers to be directly involved in their students’ education. Newspapers and educational journals from the time were full of advertisements from teaching agencies recruiting teachers for other “patriotic duties.” An editorial from Spokane, Washington declared: “Activities of various sorts are engaging school teachers who find themselves with the prospect of several weeks’ idleness before them due to the closing of schools by the health department.” Many teachers went to work for the draft board.

Without Zoom, Seesaw, and Gmail, it was harder for teachers to be directly involved in their students’ education. Newspapers and educational journals from the time were full of advertisements from teaching agencies recruiting teachers for other “patriotic duties.” An editorial from Spokane, Washington declared: “Activities of various sorts are engaging school teachers who find themselves with the prospect of several weeks’ idleness before them due to the closing of schools by the health department.” Many teachers went to work for the draft board.

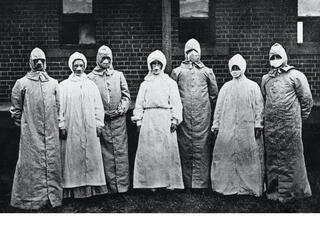

As the United States experienced a second and more severe wave of illness in the Fall and Winter of 1918, there was a shortage of nurses. Teachers who had nursing skills were recruited to help care for the sick. According to an editorial published in The Journal of Education on October 17, 1918:

As the United States experienced a second and more severe wave of illness in the Fall and Winter of 1918, there was a shortage of nurses. Teachers who had nursing skills were recruited to help care for the sick. According to an editorial published in The Journal of Education on October 17, 1918:

“When the Boston schools were closed on account of the influenza, Miss Cora Bigelow, president of the City Women Teachers’ Association, rallied all the women teachers for any service they could render the health officials, and they were badly needed.”

Many teachers took courses during this time, using the mandated pause in their teaching career for professional development. Though of course, this would have been at their own risk as online courses would not have been an option. Still, the advice to citizens to protect their health was much the same in the 1918 health report as it is today:

“Avoid needless crowding”

“Stay in the open air and in the sunshine as much as you can”

“Breathe clean air and plenty of it”

(from the Public Health Report, October 11, 1918 Influenza: Avoid it and Prevent its Spread)

But how does talking about the past help us deal with our present?

People living in 1918 lived in a world ravaged by war and pandemic. They saw their world and their daily lives change before their eyes, just as we are seeing today. And like today, some households and individuals experienced more or different hardships than others. And like today, there was fear, distress, and disagreement about how things should be done. For children, it probably felt like the world was ending and things would never be normal again.

In his essay, “Relating the English Course to the World Crisis,” published in The High School Journal in 1918, Richard H. Thornton wrote:

“Never before in the history of civilization has it been more necessary that we have an intelligent understanding of the world in which we daily live and move … Old theories and customs are being carefully examined to determine whether they meet the needs of this new age.”

So what are the needs of this new age?

For nearly six months, we as a civilization, a society, and a community have been treading the waters of what seems like an endless river of transition. Things are moving rapidly and it’s difficult to know what is around every turn or just over the horizon. It is a situation that seems somehow stagnant and unstoppable all at once.

And yet, just as Thornton decreed more than a century ago, we find ourselves examining old theories and customs -- questioning the importance of certain givens of daily life and education, and re-evaluating the necessity and propriety of certain customs. The terminal question for all remains the same: What is the safest way to ensure the social and emotional health of our future adults -- our oneday leaders and decision-makers, inheritors of the Earth and recipients of the culture we design.

We are fortunate, for we have the lessons of our ancestors and the record of their experiences to guide us. We are further fortunate on account of what we have that they did not. We have instant access to vital information (though now we are tasked with sorting the bad information from the good), and we have more options for immediate long-range communication than anyone would have dreamed during bygone eras of Social Distancing. We have more options for continuing daily life or engaging in alternate activities while maintaining safe social distance.

Our standards are higher these days, with regard to education; we expect more from students, teachers, and parents. Perhaps this is our opportunity to examine these expectations, take stock of the many advantages we have over our historical counterparts, and adjust our priorities to ensure that they truly serve our passions, our ideals, and our mission.

We’re accustomed to thinking outside the box at Spero Academy. Already, our academic and special education teams have poured their hearts, minds and souls into a truly individualized, multi-phase hybrid learning plan. Our operations team has been hard at work to perfect the health infrastructure of the building. Our educators are back with all the energy and innovation we’ve come to expect, and we are looking forward to reimagining a school year that works for each and every Spero Student.

References

“Educational News and Editorial Comment.” The Elementary School Journal, vol. 18, no. 9, 1918, pp. 641â651. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/994115. Accessed 20 Aug. 2020.

Thornton, Richard H. “Relating the English Course to the World Crisis.” The High School journal, vol. 1, no 5. Chapel Hill, N.C, May 1918

“THE WEEK IN REVIEW.” The Journal of Education, vol. 88, no. 16 (2202), 1918, pp. 437â447. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/42767153. Accessed 20 Aug. 2020.

âEpidemic Influenza: Prevalence in the United States.â Public Health Reports (1896-1970), vol. 33, no. 41, 1918, pp. 1729â1731. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/4574904. Accessed 20 Aug. 2020.

Minnesota School Boards Association. MSBA Journal. July-August 2020. https//:issuu.com/msbajournal/docs/journal. Accessed August 2020.

âUNITED STATES BOYS' WORKING RESERVE.â Monthly Review of the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, vol. 4, no. 6, 1917, pp. 991â993. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/41823463. Accessed 28 Aug. 2020.

â[Editorials].â The Journal of Education, vol. 88, no. 14 (2200), 1918, pp. 378â380. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/42767080. Accessed 20 Aug. 2020.

Letter to B.B. Jackson from Thomas Rugg, 1918 Dec 26. Minneapolis Public Schools, Superintendent's Correspondence and Subject Files, Box 4, Folder: Influenza, Minnesota Historical Society, St. Paul, MN.

â[Editorials].âThe Journal of Education, vol. 88, no. 16 (2202), 1918, pp. 434â436. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/42767152. Accessed 20 Aug. 2020.